Structural change in EU coal phase-out regions

Vassilen Iotzov

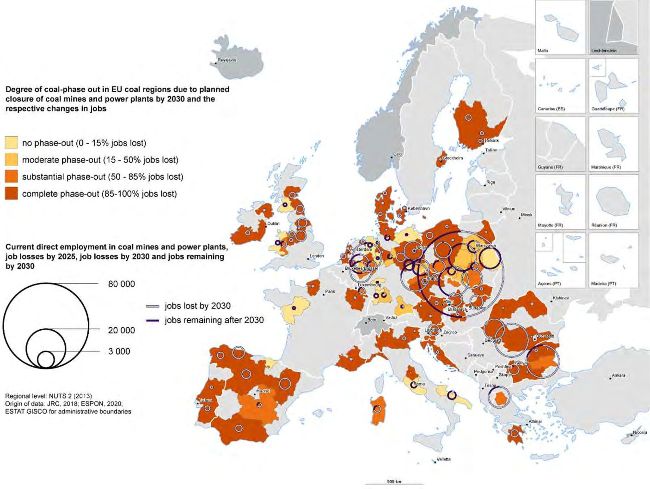

Recent debates on the just transition to a decarbonised economy have tasked policy-makers and academics alike with reconciling the different angles of the ‘just’ epithet. The phasing out of coal resonates differently in different territorial realities. Coal-dependent regions perceive that there has been a redistribution of social benefits, with marginal economic damage inflicted on a few regions. However, regions that have long embraced industrial decarbonisation, in particular, are concerned about the increasing marginal damage from coal-related activities, in which environmental costs are externalised from the incumbent industries. Financial allocations to remedy the market failure may be misperceived as a reward for regions that delay decarbonisation efforts. It is therefore important to prevent a positive feedback loop and turn attention to the place-invariant challenge that can be expected across all regional economies, albeit to different extents. The decarbonised economy commitments will bring about a paradigm shift in coal-dependent and arguably coal-independent regions alike. However, regions have different levels of potential to embark on this paradigm. In other words, regions have different levels of potential to induce structural change because of the different levels of dependency on incumbent industries, which may exacerbate the socioeconomic implications of such a paradigm shift. This is why Article 1 of the proposal for a Just Transition Fund (JTF) Regulation defines the JTF as an instrument that ‘provide[s] support to territories facing serious socio-economic challenges deriving from the transition process towards a climate-neutral economy of the Union by 2050’. Coal regions are among those regions that are particularly vulnerable, as their regional economic ecosystems are historically linked with coal extraction and power generation. The proposal for a JTF Regulation identifies 108 European regions with coal infrastructure and nearly 237,000 related jobs. In 2018, the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission estimated that the regions that will be most affected by 2030 are located in Poland, Germany, the Czech Republic and Bulgaria. By 2025, the Polish voivodeships Śląskie and Małopolskie, the Czech regions of Karlovy Vary, Ústí nad Labem and Moravskoslezský, and the German Lausitz area and the state of Nordrhein-Westfalen are projected to register more than 2,000 job losses each. By 2030, Śląskie and the Bulgarian provinces of Stara Zagora and Sliven are estimated to lose 39,000 jobs in total.

The alarming estimates have triggered an intense research–policy discourse. We plug in ESPON territorial evidence that will be useful for informed decisions on JTF actions related to research and development (R&D) investments, productive investments as well as business incubation and consultancy for firm creation and development, i.e. the first three types of activities proposed by the JTF Regulation and amended by the European Parliament. We argue that the first three types of JTF actions are crucial, as they are likely to influence parameters that best explain the variance in the structural change potential of coal-dependent regions. All other actions are likely to be pursued all across Europe within or beyond the JTF, with a comparable positive moderating effect on economic diversification.

“JTF actions related R&D, productive investments and business development influence parameters that best explain the variance in the structural change potential”

We suggest that the increasingly practised Entrepreneurial Discovery Process should be established as a JTF governance and implementation mechanism in coal phase-out regions. The principles of this process, which is associated with regional smart specialisation, are equally applicable in a process of collaborative navigation towards the most favourable corridor out of an economic path dependency.

We assimilate the popular industrial policy concepts of Open Innovation, the Innovation Commons and the dichotomy between entrepreneurial risk and uncertainty as instruments for determining a social-benefit-maximising intensity and mix of the three JTF actions in our assessment. Here, we plug in ESPON territorial evidence on small and medium-sized enterprises, the knowledge economy, foreign direct investment (FDI) and technological transformation of regional economies so as to derive a conceptual framework for the efficient use of JTF resources.

“The decarbonised economy commitments will bring about a paradigm shift in coal-dependent and arguably coal-independent regions alike”

Based on these territorial parameters, we plot the estimated position of regions expected to be most severely affected along the knowledge and entrepreneurial stock trajectories, which not only demonstrates variance in regional potential for structural change but also more importantly helps to approximate the desirable balance of the three types of JTF actions in our assessment.

Conclusions for a JTF action mix can be drawn based on the relative position along both trajectories.

Regions such as Śląskie and the provinces of Stara Zagora and Sliven, with comparably low knowledge and entrepreneurial stock compounded by higher dependency on non-local knowledge sourced from FDI, would ascertain a necessity to build up a productive and durable regional Innovation Commons, resulting in the need to channel investments towards R&D capital and inbound open innovation. The latter can be a systemised action within a Territorial Just Transition Plan that would seek to entice piloting and experimentation projects to prepare for the market roll-out of new technologies within the framework programme for research and innovation. Business incubation and consultancy must be expected to positively moderate such efforts.

“Entrepreneurial Discovery Process should be established as a JTF governance and implementation mechanism in coal phase-out regions”

Regions with better knowledge and entrepreneurial stocks will tend to resort to the Innovation Commons seeking to stimulate outbound open innovation (e.g. licensing or technology spin-offs) and consequently further diversification.

Looking at both trajectories can be particularly helpful to design adequate actions in cases of high enterprise death rates. Combined with a low level of regional knowledge stock, higher enterprise death rates may make regions such as the Trnava Region, Trenčín and Nitra more vigilant with regard to productive investments. Such investments can be positively moderated through R&D capital investments and inbound open innovation that reduce entrepreneurial uncertainty attributable to the regional knowledge stock.

On the other hand, regions such as the governmental districts of Köln and Düsseldorf, which also exhibit high enterprise death rates but perform better in terms of their knowledge stock, may find it more reasonable to invest in measures that reduce entrepreneurial uncertainty through a desirability assessment, e.g. double-track regulatory and technology-oriented public–private partnerships (e.g. publicly funded simulations of the social and environmental effects of new market-ready technologies aimed at both regulation and market roll-out).

The bottom line is that balancing investments based on territorial parameters related to knowledge and entrepreneurial stock is expected to reduce deadweight losses and engender higher social returns. This assessment is not pretending to be able to compose an accurate action mix for the coal regions that are expected to be the most severely affected but is designed to offer a conceptual framework for JTF governance.