Land Use Policies: Local Solutions for Global Challenges

Rudiger Ahrend, Andres Fuentes, Jaebeum Cho, Matteo Schleicher, OECD

Land use policies - the planning and regulation of land use - are mostly a matter for local and regional rather than national governments. So it often goes unnoticed that these policies are key to addressing some of the world's most pressing challenges. And since we don't get many chances to change the way we use land, we must think ahead so that our land use decisions today help to solve these challenges. And a regional perspective is key to addressing major global challenges, as the 2021 edition of the OECD Regional Outlook has shown.

Making land use consistent with environmental challenges

Take the environment. The United Nations has identified three big challenges that could really affect our well-being: climate change, losing plant and animal species, and land degradation. How we use land plays a huge part in all these issues. Covering the ground with artificial surfaces is bad news for biodiversity. Our soil is important too: it holds more carbon than the air and all living things combined. It can also soak up as much as 25 % of its mass in water, helping to prevent disasters and act as a long-term places prone to flooding, driven by economic incentives, despite geospatial data showing these to be high-risk areas.

Adapting land use to demographic change

Population is growing in large cities, but often shrinking elsewhere. This trend is driven by a high share of elderly people, against a background of low fertility rates and, in particular, young people moving out of rural areas to cities in search of opportunities and amenities. By 2050, it is expected that two thirds of Europe's regions will see a population decrease. This could easily amplify regional inequalities and deepen geographies of discontent, and lead to increasingly inefficient land use as certain built-up rural areas are left abandoned.

Inefficient land use makes it more expensive for governments to maintain services and amenities in these shrinking communities. With falling populations increasingly thinly spread across large areas of land, per capita costs for infrastructure and services increase. Simply put, a busline can provide more frequent service and at lower cost from a city to a water reservoir. Plus, healthy land is crucial for growing food, especially as the risk of food shortages gets higher because of climate change.

Smart spatial planning does not just aim to reduce artificial land cover. It also promotes sufficiently densely populated settlements that are well connected by public transport.

Places differ in their potential to provide essential ecosystem services, and in their incentives to protect or enhance them. Financial incentives can motivate communities to do so, while providing them with additional income. For example, Irish regions can bring back wetlands to store carbon, or Spain's Andalusia can encourage habitats for migrating birds from all over Europe.

Smart spatial planning does not just aim to reduce artificial land cover. It also promotes sufficiently densely populated settlements that are well connected by public transport. In doing so it offers the dual benefits of environmental protection and infrastructure cost savings.

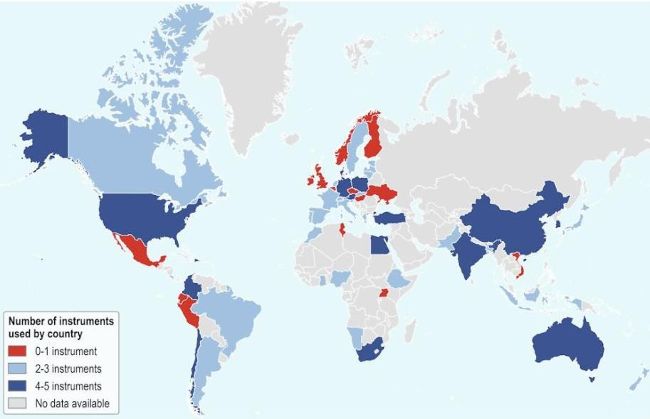

Use of Land Value Capture instruments across countries

Adapting to climate change means changing how we use land too. Too often, we see new developments in dense village than to a set of dispersed isolated homes in the countryside - not to mention the roads, water, sewage and energy supply infrastructure. In shrinking areas, policies that allow the demolition and renovation of housing, coupled with efforts to return unused land to its natural state, will need to be implemented, such as in the case of the Stadtumbau program in Germany.

Where populations are increasing, sprawling and inefficient low-density development should be avoided. Such development too often occurs in places critical for conservation. In any case, it intensifies environmental footprints by spreading infrastructure over larger areas and by increasing reliance on cars. It leads to more detached housing, with higher per capita energy consumption. Instead, growth should be accommodated by increasing density where possible to bring down the costs of services and infrastructure while preserving the environment for future generations.

Setting urban growth boundaries, when implemented with flexibility to adapt to underlying population developments and housing demand, can also be one possible approach to curb sprawl. In the areas surrounding larger cities, development needs to occur near public transit corridors with minimum density thresholds. The Finger Plan of Copenhagen, Denmark, is one example that implements such planning strategies. Split-rate property taxes that tax land at higher rates than buildings can also encourage densification. More generally, regional and national governments should embrace Green Urbanism principles, which seek to consciously reduce future emissions in urban development and create a healthier and more liveable environment for citizens.

Land use planning for affordable housing and sust ainable urban grow t h

Sufficiently dense cities make more efficient use of land, but, if buildable land is scarce, it can make housing expensive, taking a big bite out of poorer households' budgets. And dense cities require sufficient infrastructure to avoid congestion - which typically is expensive to build, too. Land use planning and land-based finance can help fund both the housing and the infrastructure.

Here is how it can work. Government actions often increase the value of land. Cities can relax planning constraints to allow taller buildings in a specific area, for example. This makes land more valuable, as developers can add new floors and sell more units. Developers who get permission to build taller buildings could be asked to provide a proportion of them as affordable housing units. Cambridge, Massachusetts, has used this tool - called inclusionary zoning - to provide more than 1 000 units of affordable housing.

The same applies to infrastructure that makes dense cities work. A new metro line increases accessibility, which makes nearby properties more valuable. The construction of a metro line in 2000 in Manila, the Philippines' capital, increased the value of land within 1 km of the line's stations by nearly USD 3.4 billion. The city government recouped some of this gain by levying a fee on landowners whose plots increased in value thanks to the metro line - a land-based finance tool called an infrastructure levy. A fraction would have been enough to pay for it, as the Manila metro cost the city USD 655 million to build.

Dense cities require sufficient infrastructure to avoid congestion - which typically is expensive to build, too. Land use planning and land-based finance can help fund both the housing and the infrastructure.

Land use planning tools provide municipalities with a huge opportunity to make their communities sufficiently dense, more affordable and more sustainable, and thereby to improve the well-being of the local populations. But they also give them great responsibility to solve some of the most pressing global challenges.

Rudiger Ahrend, Head of Economic Analysis, Data and Statistics Andres Fuentes, Senior Economist,

Head of Unit, Environmental and Land Use Economics, Jaebeum Cho, Economist and Policy analyst, Economic Analysis,

Data and Statistics, Matteo Schleicher, Junior Policy Analyst, Economic Analysis, Data and Statistics, in Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities, OECD