The Role of Public Services in the New Model of Hungarian Territorial Policy

Zsuzsanna Farkas

Kristóf Orbán

The Hungarian government aims to raise the country among the most liveable Member States in the EU, and Europe overall. Besides decreasing regional development differences, the biggest challenge of territorial policy is to moderate the migration from rural territories to cities, and, in parallel, to make the overloaded metropolitan areas liveable.

/ / im age from author

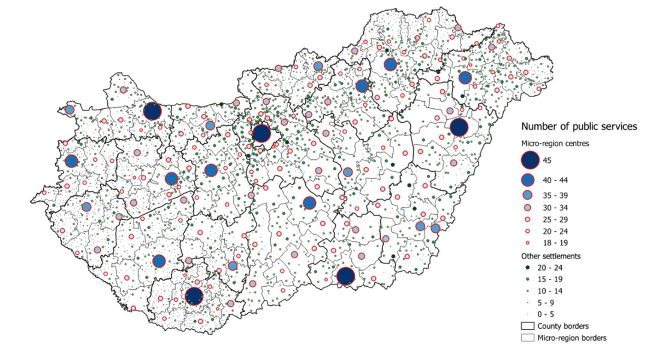

Distribution of the 45 categories of public services provided or controlled by the state across settlements, based on data provided by the Hungarian ministries

Metropolitan areas and agglomerations are growing, placing a heavy burden on public services and infrastructure, while commuting to larger cities poses an increasing challenge to transport networks. On the other hand, migration from smaller settlements is causing serious population loss in the countryside, leaving less developed areas without sufficient human resources.

Traditional territorial planning and programming generally refer to public administrative units such as regions, counties, micro-regions, etc. Evidence shows that for appropriate targeting, policymakers should understand how people use space, irrespective of administrative boundaries (a territorial extension of the place-based approach). The change in approach, therefore, entails, first and foremost, a new focus on functional areas, be they FUAs, or rural areas without a strong centre but with common problems.

Experience also shows that focusing only on growth poles and the least developed areas could only maintain, but not reduce, the differences in regional development in Hungary. Small and medium-sized towns should be strengthened in order to have local sub-centres in the countryside, where people can work, have access to public services, culture, civic activities, and so on. Without this role, there is no hope of slowing down urbanisation, which ultimately leads to an unsustainable pattern of regional development: empty countryside and congested cities.

One of the main pillars in the fight against these tendencies is the organisation and guarantee of a territorial minimum level of public (and private) services, a so-called national territorial minimum. The logic behind this is that if good services are provided, people will choose to commute rather than leave rural areas, while investors will also prefer places where public and private services are sufficient. Of course, all this is true only if the other two pillars, job creation and transport networks, also serve this purpose well.

In addition, well-organised public services in the least developed areas have positive externalities. They create jobs that can keep the educated population in the region, they provide a model of institutional and communication culture for the local society, and they provide security for the most vulnerable social groups.

Screening of (public) services

Since the summer of 2023, the Ministry of Public Administration and Regional Development has been coordinating a study involving all the relevant ministries. Based on the data received, in the first phase, 45 categories of services provided or controlled (financed or regulated) by the State were selected for review. Particular emphasis was placed on the following provisions:

- healthcare,

- education, vocational training, and higher education,social services, childand family protection,

- ambulance, police, fire and disaster management

- culture,public administration,

- transport,

- jurisdiction, legal services,postal services, andtax authorities.

Small and medium-sized towns should be strengthened in order to have local sub-centres in the countryside, where people can work, have access to public services, culture and civic activities

We have also included some services that are partly independent of the state, but are in some way controlled (financed or regulated) by it, such as sports facilities, pharmacies, veterinary services, utilities, or industrial parks, as well as certain local services provided by the municipalities. In the next (ongoing) phase of the research, we intend to analyse the distribution and availability of basic private services that are vital to citizens' daily lives, such as shops, financial services, bars/ restaurants, petrol stations, and so on.

if good services are provided, people will choose to commute rather than leave rural areas, while investors will also prefer places where public and private services are sufficient .

The map below shows the distribution of the 45 categories of (public) services provided or controlled by the state across settlements, i.e. the variety of services available on the territory of each municipality.

The map reflects the functional hierarchy of the Hungarian settlements. It shows, among other things, the low diversity of public services in certain county (NUTS3) centres and micro-regional (LAU1) centres, while we find a higher diversity of services in certain towns belonging to metropolitan areas, despite their lower status in the hierarchy of settlements.

It is important to point out the fragmented structure and lower number of services in the north-eastern and south-western parts of Hungary, where settlement density is high but settlement sizes are small, which causes relevant difficulties in organisation and accessibility. The low-profile functioning of the small and medium-sized towns in the inner and outer peripheries can also be observed, which goes hand in hand with the lack of their economic organisation potential.

Another key aspect of the organisation of public services is their accessibility. Our research has measured the accessibility of the nearest service providers by car from each settlement, and in the next phase, research will be extended to analyse the accessibility of public transport. This is also part of measuring the size of the "natural" service area of a city/ town, which is important for fine-tuning the legislation on the territorial scope of service provision.

How to define this territorial scope is a relevant policy challenge, as the functional approach would imply a certain legislation that needs to be reconciled with the long-established territorial structure of certain public services and the well-functioning territorial network of government offices that integrate a large number of public services at county and micro-regional levels.

Zsuzsanna Farkas, head of department, Kristóf Orbán, senior expert, Ministry of Public Administration and

Regional Development, Hungary